Fentanyl misinformation: Why claims by Bloomington Police chief are part of troubling trend

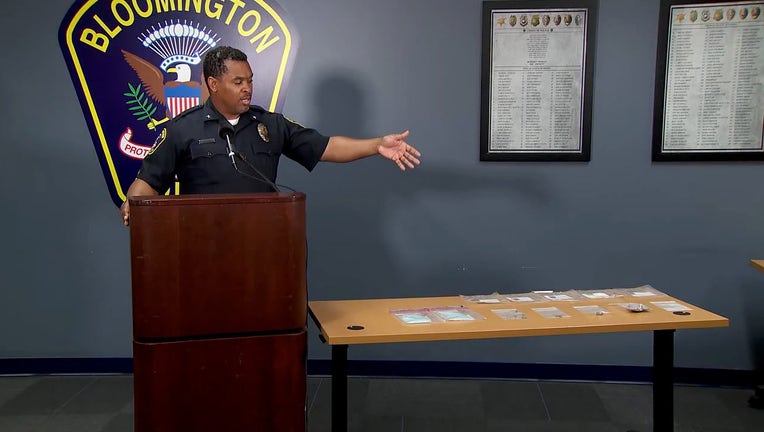

Bloomington Police Chief Booker Hodge gave a press conference last Thursday in which he said opioids his officers had seized were "Narcan-resistant." (FOX 9)

BLOOMINGTON, Minn (FOX 9) - Misinformation that potent forms of fentanyl and powerful synthetic opioids are completely resistant to the anti-overdose drug naloxone or require a higher dose persists among first responders, particularly law enforcement, despite studies proving otherwise.

Health experts fear the spread of misinformation around fentanyl could cause confusion among first responders and contribute to drug users losing trust in the medical establishment, making them less likely to seek medical help.

MN Poison Control sets the record straight on fentanyl misinformation: Narcan works

The director of the Minnesota Department of Poison Control wants the public and first responders to know that the anti-overdose drug naloxone, also known as Narcan, works, even for reversing overdoses caused by new, more potent forms of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids.

However, since at least 2017, there has been a steady drumbeat of local news reports – almost all exclusively quoting law enforcement – about fentanyl or opioid synthetics being "Narcan-resistant" resulting in fear-inducing, false headlines that suggest Narcan (the name brand of naloxone) won't save you from certain types of fentanyl.

Bloomington Police chief spreads misinformation, promises to do better

Last week, this trend arrived in Minnesota when Bloomington Police Chief Booker Hodges held a press conference to announce his officers had found a large amount of illicitly produced synthetic opioids during an arrest. He referred to the drugs as "Gray death," a loose slang term most commonly used to refer to the combination of fentanyl, carfentanil and another powerful synthetic opioid, U-47700.

Hodges said the drugs seized were "Narcan-resistant," despite the fact overdoses from all three drugs, even when they are combined, can be treated with naloxone.

In a follow-up interview with FOX 9 on Saturday, Hodges acknowledge Narcan could treat overdoses from synthetic opioids.

"Narcan is still effective with these new combinations of fentanyl, such as this ‘Gray Death,’" he said.

However, in the interview, Hodges went on to add it was his understanding officers would need as many as 10 doses of Narcan to treat overdoses from "Gray Death", which is more doses than officers typically carry with them. In most departments, officers carry a kit with two 4 mg doses of the nasal spray.

When asked where the number 10 came from, Hodges cited online and law enforcement sources. When pressed, he concluded he needed to look at the research more closely.

"Some of us in all professions sometimes get outside of our swim lanes, and we should do a better job of staying in our swim lanes. And I'll do a better job of that moving forward," Hodges told FOX 9.

Upward trends

This is a topic Lucas Hill, the director of the Pharmacy Addictions Research and Medicine Program at the University of Texas, has studied closely.

In 2020, Hill noticed two overlapping trends concerning the synthetic opioid fentanyl he thought warranted closer inspection.

The opioid epidemic, which was killing tens of thousands of Americans every year, was entering a new, even deadlier phase. Opioid overdoses spiked during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with synthetic opioids, primarily illicitly manufactured fentanyl, overtaking overdoses caused by heroin and prescription-strength opioids like Oxycodone.

RELATED: Fentanyl a driving factor in Minnesota's record overdoses deaths in 2021

At the same time, studies were showing that increasingly, first responders were responding to the surge in more potent forms of fentanyl, often combined with other synthetic opioids, by increasing the doses of naloxone. When administered, typically as the nasal spray with the brand name Narcan, naloxone can quickly reverse opioid-induced depression of respiratory depression, allowing patients to breathe again.

Drug manufacturers were gearing up to meet the demand — that same year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new 8 mg dose of naloxone nasal spray, a step up from the 2 mg and 4 mg sprays then available, as well as a higher dose injectable form of naloxone.

But Hill had a question: were these higher doses really necessary? There was a lot at stake, in terms of understanding how best to treat overdoses and in helping state governments understand how to effectively direct funds meant for the purchase and distribution of naloxone to first responders and other groups who treat drug overdoses.

"It was really the marketing of that first 8 mg intranasal product that made us stop and think we need an answer to this question because state opioid response programs, departments of health in various states are going to be faced with a tough decision about which product to purchase when they've got millions of dollars on hand to buy an opioid antagonist. And we wanted to help them understand and separate myth from reality in terms of these higher-dose products," Hill told FOX 9.

Hill and a team of teachers conducted a literature review, diving into the available studies and data on naloxone dosage in the treatment of overdoses related to synthetic opioids. Their findings were definitive.

"Well, I think the first and most important question is, do we actually need higher-dose products? And we came away with the answer: No," he said.

Other studies have reached similar conclusions, but Hill cautions that the science on illicit drugs is always evolving as the drugs themselves change. The ideal dosage level and protocol for naloxone is still a subject of debate among researchers, with another paper published in 2020 suggesting a slightly higher dosage range, or a shift from 2 mg and 4 mg doses to 5 mg and 10 mg doses.

But nothing in that debate explains or substantiates the rumors among law enforcement that potent forms of fentanyl and powerful synthetic opioids like carfentanil are either completely resistant to naloxone or require the kind of high dosage range suggested by Chief Hodges.

Fentanyl mythology

Hill sees a connection between Hodges' statements and another false rumor that circulated among law enforcement and local media earlier this year: that first responders could overdose from touching the drug.

"There is a there's a lot of mythology surrounding these potent synthetic opioids, like fentanyl and carfentanil, and it includes that people are afraid if they're just near the drug or they get a little bit on their skin, that they might accidentally ingest it somehow and experience harm. And that is an absolute myth; that can't happen. That has not happened," he said. "But even that myth has been shown to be a misunderstanding held by most law enforcement officials in the United States."

RELATED: 2 St. Paul police officers treated for fentanyl exposure; police HQ partially evacuated

He adds:

"While I empathize with law enforcement and the position and the stresses that they're put in while trying to help respond to the opioid crisis in our communities, I have to address the fact that these are just not real concerns, and we can actually help keep law enforcement safer and reduce the workload on them by getting the truth out there."

What’s driving the increase in dosage?

Hill and others have argued the increase in naloxone dosages administered by first responders may be driven by understandable concern.

"If you have been told that it's going to take multiple doses, then you're primed to give multiple doses, and you're unlikely to wait the 3-5 minutes between doses that it can take to really see the impact of the previous dose," Hill explains. "You might decide to error on the side of administering more because you're just so confident that more is going to be needed, and it's a positive reinforcement loop."

Hill believes another contributing factor is how the illegal drug supply is increasingly contaminated with other highly potent non-opioid sedatives.

For example, in August, NPR reported health officials in Central Massachusetts started to notice Xylazine, a powerful animal tranquilizer, showing up in fentanyl.

Xylazine is not an opioid, and first responders began to notice patients who had ingested both drugs responded differently to treatment. As the NPR piece noted: "Squirting naloxone into someone's nose won't reverse a deep Xylazine sedation — the rescuer won't see the dramatic wake-up that is more common when giving Narcan after an opioid overdose."

Hill explained:

"Administering naloxone is going to reverse the opioid part of that overdose. But the person may still appear to be very sedated, and it could take a more trained medical eye to be able to specifically know that they are breathing, even though they aren't responsive. And an additional dose of naloxone isn't really necessary," he said.

High stakes

Law enforcement administering more naloxone than needed is not without cost, Hill says. Naloxone can cause patients to experience more severe withdrawal symptoms, and if patients suspect that they may be given more Naloxone than needed, they may be more reluctant to seek medical attention.

"So the stakes here are very high, and it's important that we don't underestimate the value of listening to people with lived experience and the organizations that directly engage with people who use drugs to ensure that we're embracing strategies that are going to maximize effectiveness," he said