Missing and murdered: 'Where's the outrage?'

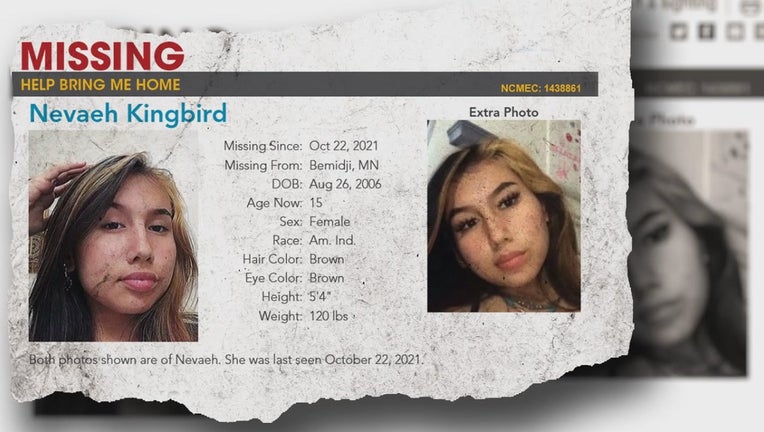

Nevaeh Kingbird has been missing since October 2021.

(FOX 9) - The epidemic of missing and murdered Native American women has been largely ignored for generations across the country. However, for many affected indigenous communities, the problem is deeply personal.

Monte Fronk is in charge of emergency management for the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe. However, he also has another title.

Missing and murdered: 'Where's the outrage?'

The epidemic of missing and murdered Native American women has been largely ignored for generations across the country. However, for many affected indigenous communities, the problem is deeply personal.

"I am a Native father of a murdered daughter," Fronk said.

Fronk candidly shares the story of his daughter Nada – who lived a harrowing yet short life.

"She was passionate. She was resilient. She was strong," Fronk said.

Fronk tells the FOX 9 Investigators Nada was diagnosed as a "second generational fetal alcohol child," which often led her down dangerous or risky roads in life.

"She kind of went from one facility to another facility to another facility," Fronk recalled.

At the age of 14, Nada became a runaway. The young girl’s face once plastered on a missing flier would become a face found in online advertisements as she became victim of human trafficking for almost two years.

"You live with it 24-7 wondering if your child is OK, you know, are they still alive?" Fronk said.

Nada was eventually spotted and rescued by law enforcement in the Twin Cities. She managed to finish high school and re-connected with her family.

Fronk emotionally recalls one conversation with his daughter: "Nada looked at me and said ‘Dad, the only reason I am alive is because of you. For everything I did to make you and mom give up on me, you never did,’ and as a father, that's a great moment that I'll never forget."

Nada continued her young adult life in the Twin Cities until May 26, 2021, when Brooklyn Park Police were called to her apartment after reports of gunfire.

"They found what appeared to be a murder-suicide. And unfortunately, the victim was my daughter at age 24," Fronk said.

Nada was shot multiple times by her boyfriend. However, the reason remains a mystery as the investigation remains open.

Her father is grateful he had the chance to give his daughter a traditional funeral.

"I had closure and I could get my daughter on her traditional Ojibwe spiritual journey," Fronk reflected.

However, he acknowledges the countless Native American families who don’t get that same opportunity.

"As Native people, we feel for all of our relatives, and for those of us who have walked this path, we always feel because again, that other Native family may never have closure or may never have an answer," Fronk said.

The crisis across Indian country

According to a Minnesota task force report, American Indian women and girls are seven times more likely to be murdered than their white counterparts.

"We continue to hear story after story of our people going missing – and where’s the outrage?" asked Nicole Matthews, Executive Director of the Minnesota Indian Women’s Sexual Assault Coalition. "What becomes so disheartening is to really feel like we're so devalued and so invisible."

One troubling disparity Matthews points out is the difference in the response to reports of the missing. For example, the disappearance of Gabby Petito and her subsequent murder in 2021 drew national headlines – a reaction often absent for victims of color.

"We don't have nationwide outrage because our people are missing. We don't have people who are talking about it in every community. I bet you most people outside of indigenous communities cannot name five indigenous women who've been missing or murdered. I think that's a problem," Matthews stated.

In Minnesota, as many as 54 American Indian women were actively missing in any given month from 2012 through 2020, according to the state’s task force report. However, it’s widely accepted that the problem is vastly under-reported.

New state focus

However, there is work underway to bring the issue out of the shadows, including a new state office for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives (MMIR). It will be based in St. Paul and is expected to be fully staffed and operational later this year.

Juliet Rudie will serve as the MMIR director. She has almost 28 years of experience in public safety. Her first day on the job is February 28.

At the Minnesota State Capitol, Lieutenant Governor Peggy Flanagan, among Native American women, pushed for progress..

"For too long, frankly, Native people have been seen not as people, but as numbers or as a problem to be solved by government, and now that we are in positions within these same systems, it is harder to dismiss our humanity," Flanagan said. "We are in a moment where we just cannot lose momentum."

The new MMIR office will take more than 160 pages worth of recommendations developed by the state’s task force and work toward real-life solutions.

"My hope and, you know, the charge is to make sure that this office is looking at the systemic changes that need to happen, so this crisis of missing and murdered indigenous relatives is stopped," Flanagan said.

However, tackling the problem is complicated – from the patchwork of state, federal and tribal jurisdictions and the laws that govern them to addressing how the sexualization and abuse of Indigenous women and girls has deep roots in colonialism. Additional hurdles include a lack of resources and culturally relevant training.

"We cannot afford to wait. I am proud of how quickly all of this came together and I think… sometimes government moves slowly," Flanagan said. "The fact that we have the task force in 2019, the report in 2020, and then created this office in 2021 and now it will open in 2022, that’s fairly fast, but it’s not fast enough for folks like Nevaeh Kingbird who is a 15-year-old girl who’s a Leech Lake member who went missing from Bemidji four months ago."

Many advocates, including Matthews, acknowledge the momentum.

"I wouldn't be doing the work that I do unless I really believed we can get there," said Matthews. "That's the stuff that gives me hope -- is to believe that we can get there, to believe that we can and have the ability and the capacity to put an end to this violence."