Minnesota Untold: Looking for 'Little House'

Minnesota Untold: Looking for 'Little House'

On the southern plains of Minnesota, in Redwood County, you’ll find a legendary small town, an almost mythical place, called Walnut Grove.

WALNUT GROVE, Minn. (FOX 9) - On the southern plains of Minnesota, in Redwood County, you’ll find a legendary small town, an almost mythical place, called Walnut Grove.

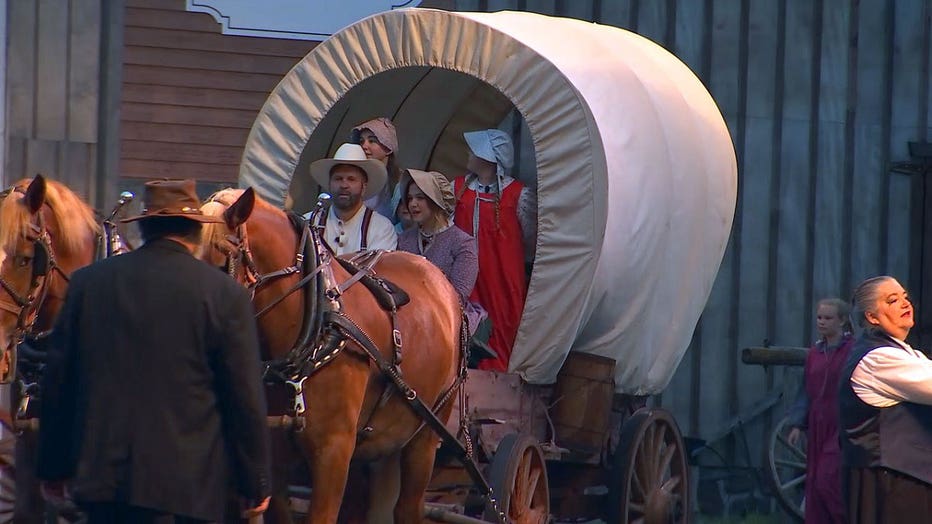

Visitors from around the world still make the pilgrimage to Walnut Grove during two weekends in July for an annual pageant, where you’ll find young girls dancing in prairie skirts and sun bonnets and playing along the banks of Plum Creek.

The bucolic fantasy inspired by a young girl from long ago, and the global phenomenon is known as "Little House on the Prairie."

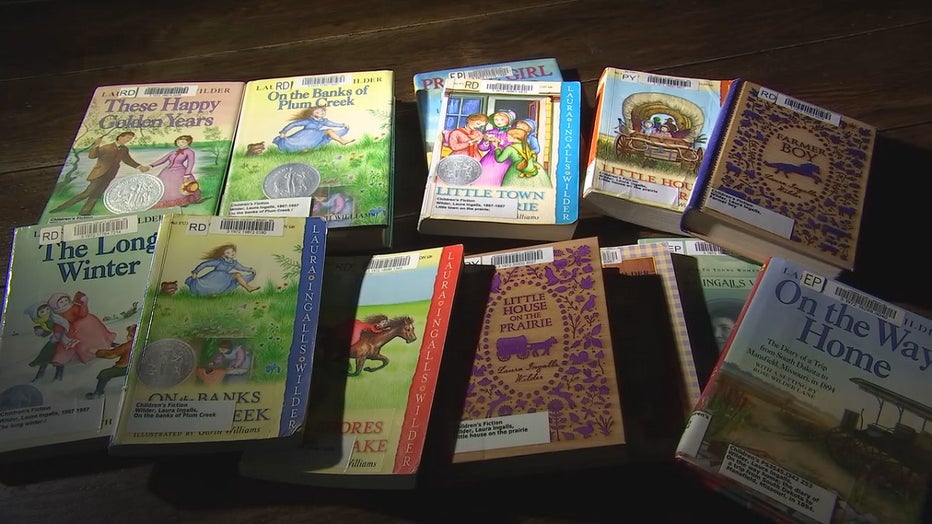

The Little House on the Prairie book series tell the story of pioneer life in Minnesota but maybe not the whole story. (FOX 9)

But the real story of author Laura Ingalls Wilder — the child, the woman, and her legacy — is more complicated than one might imagine.

The popular television show, which ran for eight seasons in the 1970s and early 80s and is still in syndication, was a rose-colored embellishment of Wilder’s children’s books.

The nine ‘Little House’ books have together sold 60 million copies and have been translated into 45 languages. In other countries, many use the books to learn English. Even Saddam Hussein was reportedly a fan of Little House.

Laura Ingalls Wilder (Supplied)

Some of the most memorable storylines were set in Walnut Grove, Minnesota, where Wilder lived from the age of 7 to 11.

"I can go anywhere in the world and say, ‘Walnut Grove,’ and then say, ‘Little House on the Prairie,’ and they say ‘Oh my God, you live there? What was that like?" said Amy Foster, who grew up in Walnut Grove and runs the Laura Ingalls Wilder Museum.

The museum has a replica of the ‘dugout’ home where Wilder lived with her family, an old schoolhouse, and the real-life general store, that ‘Pa’ helped build.

"The big thing that happened here is she was able to go to school had lots of friends, but the big significance is it was the time her sister went blind," Foster said.

Becoming her sister Mary’s narrator for the world around them would turn Wilder into a gifted storyteller. But in her books, she often left out the grittier details of frontier life.

Sign for Walnut Grove, Minnesota (FOX 9)

Debt, drought, and locusts

Wilder was born in 1867, a couple of years after the Civil War, in Pepin, Wisconsin. She was the middle of three sisters.

Over the next decade, her father, Charles Ingalls, dragged the family by covered wagon across the Midwest, in the great land rush brought on by the Homestead Act.

In 1868 the family traveled to Missouri looking for suitable land to farm. The following year the Ingalls went to Missouri.

By 1869, the Ingalls were in Kansas, where according to historical accounts they were squatters, illegally occupying land that was part of the Osage Indian Reservation.

By 1874, they were back in Walnut Grove, MN, where Charles failed miserably as a farmer, struggling with debt, drought, and in 1875 a biblical plague of locusts that destroyed what would have been a bumper crop of wheat.

The family became so destitute Charles applied for a state handout, testifying under oath that he was "wholly without means." He received a barrel of flour.

Governor John Sargent Pillsbury warned farmers like Ingalls about accepting handouts, "weakening the habit of self-reliance." For the starving, Pillsbury recommended a day of prayer.

After yet another invasion of locusts, Charles Ingalls packed up his family and went to Burr Oak, Iowa (1876-1877), where ‘Pa’ tried his hand at running a hotel. But in Iowa, Charles only ran up more debt, and along with the rest of the family, skipped town in the middle of the night.

The Ingalls returned to Walnut Grove in 1878, staying for another year before moving on to De Smet, in Dakota Territory, where Laura would meet her future husband, Almanzo Wilder.

"Their life wasn’t perfect, and Pa really did struggle with surviving," Foster said.

(FOX 9)

A History Problem

Wilder’s Little House books are filled with colorful characters, like the spoiled Nellie. But actual people of color played secondary roles in Wilder’s world.

In Little House on the Banks of Plum Creek, Wilder describes a neighbor, Ms. Scott, and her hostility toward Native Americans.

"The only good Indian was a dead Indian. The very thought of Indians made her blood run cold." She said, "I can’t forget the Minnesota massacre," Wilder writes.

Foster, director of the Laura Ingalls Wilder Museum, said context is important.

"It was a period of time when people didn’t understand those injustices," Foster said. "When Laura writes about Native Americans it’s about how mom did not like them or Ms. Bost did not like them, it wasn’t what she said, it was someone else speaking."

The ‘untold’ story of ‘Little House’ is the very real history of Minnesota.

A few years before Wilder was born, hundreds of Dakota died from disease and starvation after the U.S. Government reneged on annuity payments from treaties.

It led to the Dakota War of 1862, often referred to as the Minnesota massacre.

In nearby New Ulm, hundreds of settlers, men, women, and children, were killed.

In Mankato, 38 Dakota were hanged. It remains the largest hanging in U.S. history.

But Wilder whitewashes much of that dark history, instead idealizing a wide-open prairie.

"There were no houses. There were no roads. There were no people," Wilder writes in ‘Little House in the Big Woods."

That’s because the people – the Dakota -- had been driven out, forcibly removed, a bounty placed on their head. For many historians, it was nothing short of genocide.

The Laura Ingalls Wilder Museum (FOX 9)

Reevaluating Little House

Because of Wilder’s stereotypical depiction of Native Americans, in 2018 the American Library Association announced it was changing the name of its Laura Ingalls Wilder Award to the Children’s Literature Legacy Award.

The association said Wilder’s work contained "dated cultural attitudes toward Indigenous people and people of color that contradict modern acceptance, celebration, and understanding of diverse communities."

Writing about the decision in The Atlantic, Amy Fatzinger, a professor of Native American Studies at the University of Arizona, suggested the Little House books "fall short of contemporary expectations for children’s literature."

Fatzinger writes that children reading the Little House books today "may need guidance from adults to navigate the difficult themes she raises."

One of Fatzinger’s alternative suggestions is Minnesota author Louise Erdrich’s Birchbark House series, which is centered on an Ojibwa girl.

Laura Ingalls Wilder festival

Faith, Family, and Friends

Many overlook the stereotypes and casual racism in Wilder’s work, focusing instead on its literary qualities.

Advocates for the books say they also contain timeless emotional truths, like how Laura cared for her blind sister and her blind devotion to her father, Charles.

Bill Richards, a former high school principal in Walnut Grove who’s been running the annual pageant for 18 years, says the books’ enduring power is attributable to three things: "faith, family, and friends."

"There are so many other stories that are dark and bleak. I think people would prefer, unless you were a horror movie fan, something uplifting. What they experience is so difficult. They are looking for some hope," Richards said.

Some events were apparently too tragic for Wilder to write about.

Wilder never wrote about her infant brother, Freddy, who died. She also left out the domestic violence she witnessed.

Rose Wilder Lane

A Daughter & Editor

Wilder began writing the Little House books during the Great Depression of the 1930s, when she was in her 60s.

The books offered an escapist fantasy of frontier life during a troubled time.

It has been said that Wilder took the shame out of poverty.

In recent years, Wilder scholars have focused on the role of her daughter, Rose, as her editor.

Richards admits, Rose "had an agenda."

Rose Wilder Lane was herself a writer of some fame.

She was also extremely conservative.

Under Rose’s editing, the Little House stories were framed as a morality tale of self-reliance and family values, according to Prairie Fires: The American Story of Laura Ingalls Wilder, a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography by Caroline Fraser.

Rose insisted the Little House books were true, but privately admitted they were a literary trojan horse, indoctrinating children with conservative values, writing: "How much good my mother’s books have been – and are – doing in their quiet way."

"Not the whole truth"

Laura Ingalls Wilder died in 1957, just a few days after her 90th birthday.

In the end, she had achieved a kind of wealth and success her father couldn’t even dream of.

Today, there are Wilder museums – and gift shops -- in almost every town she lived.

But it wasn’t all prairie skirts and sun bonnets.

And the fiction of Little House is no substitute for the true history of the time, with all of its moral ambiguity.

Wilder herself once famously said: "All I have told is true, but it is not the whole truth."

You could add, it’s also not the only story.

And many of those stories, didn’t have a happy ending.