Minnesota Untold: After the Plague

(Supplied)

MINNEAPOLIS (FOX 9) - At Minneapolis’ Pioneers and Soldiers Memorial Cemetery, the oldest in the city, about two dozen graves mark a dark chapter in Minnesota history, the Spanish Flu of 1918.

Cemetery Historian Sue Hunter-Weir knows the stories of many of them.

Minnesota Untold: After the Plague

At Minneapolis’ Pioneers and Soldiers Memorial Cemetery, the oldest in the city, about two dozen graves mark a dark chapter in Minnesota history, the Spanish Flu of 1918.

Two of those graves belong to Percy Gould and his wife.

According to Hunter-Weir’s research, the couple was among the first Minnesotans to succumb to the flu in 1918. They died ten days apart, leaving three children behind.

One hundred years later, the similarities are striking.

"I mean, there was a story in the Washington Post last week about a young couple in California who died within two weeks of each other, and they left five children behind." she recalled.

Daniel and Davy Macias lived in southern California.

A century’s worth of proof, that pandemic deaths aren’t just about the here and now. The loss of loved ones will affect families for generations.

"I think what people need to really remember is that this pandemic is not an individual crisis. I mean, it certainly is for the person who dies, but it's more far-reaching than that, that the consequences ripple down," Hunter-Weir told FOX 9.

She saw that ripple effect in her own family when her grandmother died from the 1918 flu, leaving her mother behind.

"I think it affected her whole life. She never really knew her mother, it disrupts family stories in really interesting ways."

(FOX 9)

Nurse Comforts Children

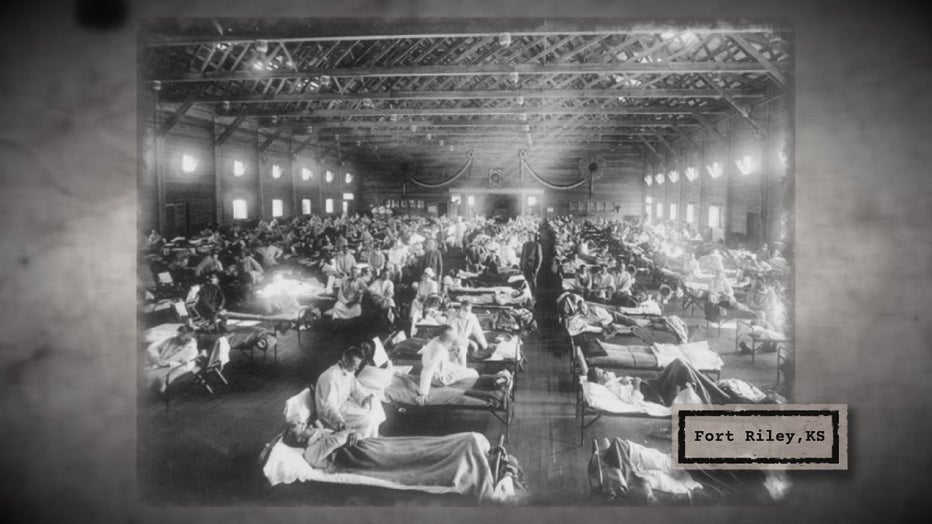

The 1918 influenza pandemic is believed to have started in Kansas from soldiers fighting in WWI.

According to the Minnesota Historical Society, Fort Snelling Hospital reported its first case in September of 1918.

The timing was awful. Medical staff across the country was already stretched thin because of the war. Nurses became indispensable.

Former Hennepin History Museum intern, Hannah Dyson, recently researched the story of nurse-in-training Pearl McIver.

The 23-year old was pulled to the front lines at the University of Minnesota Hospital in 1918 when the pandemic hit.

For weeks, she was the only one working the overnight shift in the pediatric ward. She wrote about it some 50 years later.

"Often the sick and frightened children were bundled up and taken to the university hospital in paddy wagons," McIver wrote. "Rules of the hospital required all personnel to wear masks, close-fitting caps, and white gowns, supposedly to prevent the staff from contracting influenza. Imagine the terror of these children to find themselves in a strange environment among a bunch of ghosts."

Dyson said McIver took matters into her own hands, taking off her mask to comfort the children.

"She decided that she would pick up the children out of their cribs and take them to the rocking chair and soothe them to sleep. That was not the guidance that she had from the hospital because you really didn't pick up the children," Dyson recalled from her research.

McIver put the lives of those children before her own, the same way today’s frontline workers stepped up for us during the early months of COVID-19, with limited PPE and no vaccine.

(Supplied)

Balance between Government Authority and Personal Freedoms

In 1918, the Minneapolis Health Commissioner, Dr. H.M. Guilford, rolled out some heavy-handed restrictions.

He banned public gatherings and shut down businesses and schools. People were confused and skeptical, especially because the rules were much more lax in neighboring St. Paul.

At the same time, the equivalent of a "super spreader" event was breaking out in Minneapolis.

The dorms at the University of Minnesota were full of young men training to become soldiers for the war and became a breeding ground for disease.

A century later the same hesitancy toward science, medicine and mandates can be seen and the same tendency to gather, at any cost.

In August of 2020, more than 400,000 people descended on South Dakota for the Sturgis motorcycle rally, feeling it was safe.

Contact tracing afterward found at least 649 cases of COVID, across the U.S. because of the big event. In Minnesota, one person died, and four others were hospitalized.

Rich Danila is Minnesota’s Deputy Epidemiologist. He and his team have been helping shape the state’s public health protocols, around COVID and just like Dr. Guilford, they have their share of critics.

"In our wildest dreams, no one ever imagined that there would be a politicization of something as simple as wearing a cloth mask," he told FOX 9. "It also never dawned on us that people would, not trust science in terms of vaccination. If someone, if you or your loved one gets cancer, you go to the doctor. Of course, you want the best cancer treatment, the most modern treatment cure you could. So, it boggles our mind."

Politics aside, most people agree science is at the heart of stopping the spread of any pandemic. That said, it's never a "perfect science."

"I think we still have a long way to go before we can even see the light at the end of the tunnel for the pandemic," Danila said.

The Numbers

Officially, the COVID-19 pandemic is the deadliest disease event in American history, surpassing the Spanish Flu of 1918.

Back then, an estimated 675,000 people died in the U.S.

As of mid-November, COVID deaths in the U.S. number 764,882.

However, the current population is three times what it was just before 1920.

In the late 1900s record keeping was not as precise as it is now. Experts believe the number of people who died back then, could be much higher than what is reported.