John Lewis: ‘Good troublemaker’ and tireless activist — a look at the life of the civil rights icon

ATLANTA - Rep. John Lewis was known as one of the foremost prolific advocates for securing civil liberties, protecting human rights and building what he called “The Beloved Community” in America, according to his biography.

After a battle with pancreatic cancer, Lewis died at the age of 80 on July 17, but his legacy left an indelible mark on the history of the nation.

RELATED: Rep. John Lewis, lion of Civil Rights Movement, dies at 80

The representative from Georgia’s 5th Congressional District, known for getting into “good trouble,” was outspoken on civil rights issues, spending a large part of his life peacefully protesting and seeking justice and equity for the underrepresented.

A timeline of his life’s work showcases Lewis’ commitment to the tireless pursuit of equality over more than six decades, from the early days of the civil rights movement to 2020.

Feb. 21, 1940

Born in Troy, Alabama, John Lewis grew up in a segregated society where, even as a young boy, he was inspired by the activism surrounding the larger civil rights events that happened in his home state.

1955-1956: Montgomery Bus Boycott & Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott, a 13-month protest that started in December of 1955 when John Lewis was 15 years old, ended with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling segregation on public buses unconstitutional. Lewis cited the impact of the boycott, along with the words of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., as some of the key elements that pushed him to get involved in the civil rights movement, according to his biography.

"It was during the Montgomery Bus Boycott that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., then a young preacher and the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, emerged at the forefront of the movement for civil rights and social justice in America," Lewis said on the 59th anniversary of the boycott. "Today the work that Rosa Parks began and Dr. King directed is studied by non-violent activists all over the world, who use it to discover the ways and the means they can use to challenge injustice in every corner of the globe."

"We are fortunate that the example of Rosa Parks and Dr. King are so accessible to us as Americans. They are no longer with us, but the ideas they stood for define a great legacy and the work they have left for us to do still remains... What they did and how they did it can inform the activism of today and help push our nation forward into the next phase of our destiny until we reach the day when this nation becomes a truly multi-racial democracy that values the dignity and the worth of every human being."

1960: John Lewis and others organize citywide sit-in to end segregated lunch counters

In one of his first notable demonstrations during the civil rights era, Lewis organized a sit-in as a student attending Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee in response to the segregated lunch counters across the state on Feb. 13, 1960.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), to which Lewis was was appointed chairman, was largely responsible for organizing student activism during the civil rights movement, including sit-ins and other activities.

RELATED: Congressman John Lewis: "Be constructive, not destructive"

1961: John Lewis and the Freedom Riders

During the Freedom Rides, which began in May of 1961, Lewis volunteered to help challenge the segregated interstate bus terminals across the South, and even risked his life on more than one occasion.

Lewis, then 21 and already a veteran of sit-in protests, was the first Freedom Rider to be assaulted, according to Smithsonian Magazine. While trying to enter a whites-only waiting room in Rock Hill, South Carolina, two men set upon him, battering his face and kicking him in the ribs.

Less than two weeks later, he joined a ride bound for Jackson. "We were determined not to let any act of violence keep us from our goal," Lewis said. "We knew our lives could be threatened, but we had made up our minds not to turn back."

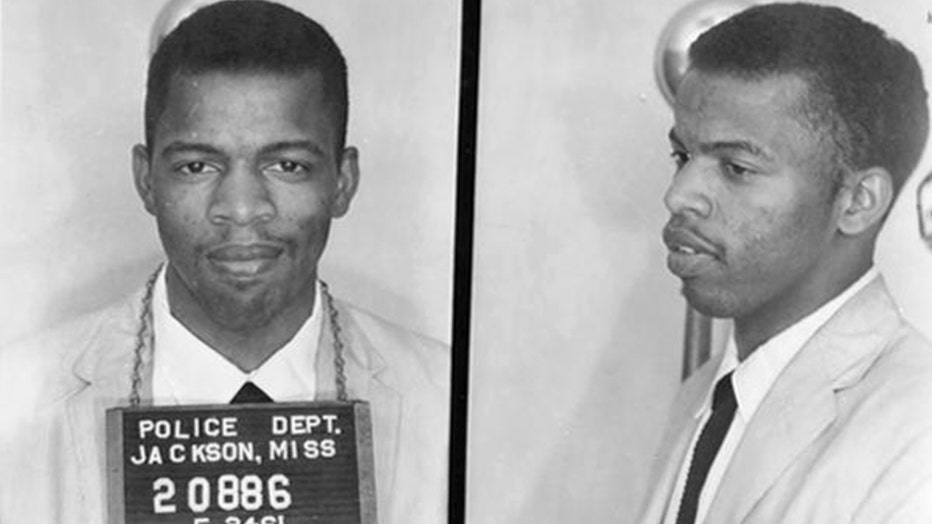

A mug shot of civil rights activist and politician John Lewis, following his arrest in Jackson, Mississippi for using a restroom reserved for "White" people during the Freedom Ride demonstration against racial segregation on May 24, 1961. ((Photo by Kypros/Getty Images))

1963: March on Washington

By 1963, John Lewis was named one of the “big six” leaders of the civil rights movement. At the age of 23, he helped organize and was a keynote speaker at the historic March on Washington in August 1963, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, according to his biography.

“A first draft of Lewis’ prepared speech, circulated before the march, was denounced by Reuther, Burke Marshall, and Patrick O’Boyle, the Catholic Archbishop of Washington, D.C., for its militant tone,” according to The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

“‘In the speech’s original version, Lewis charged that the Kennedy administration’s proposed Civil Rights Act was ’too little and too late,’ and threatened not only to march in Washington but to ‘march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We will pursue our own ‘scorched earth’ policy’. In a caucus that included King, Randolph, and SNCC’s James Forman, Lewis agreed to eliminate those and other phrases, but believed that in its final form his address ‘was still a strong speech, very strong,’” the Stanford MLK institute continued.

According to Stanford, the march pressured the John F. Kennedy administration to introduce a strong federal civil rights bill in Congress.

“After the march, King and other civil rights leaders met with President Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson at the White House, where they discussed the need for bipartisan support of civil rights legislation. Though they were passed after Kennedy’s death, the provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 reflect the demands of the march,” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University wrote.

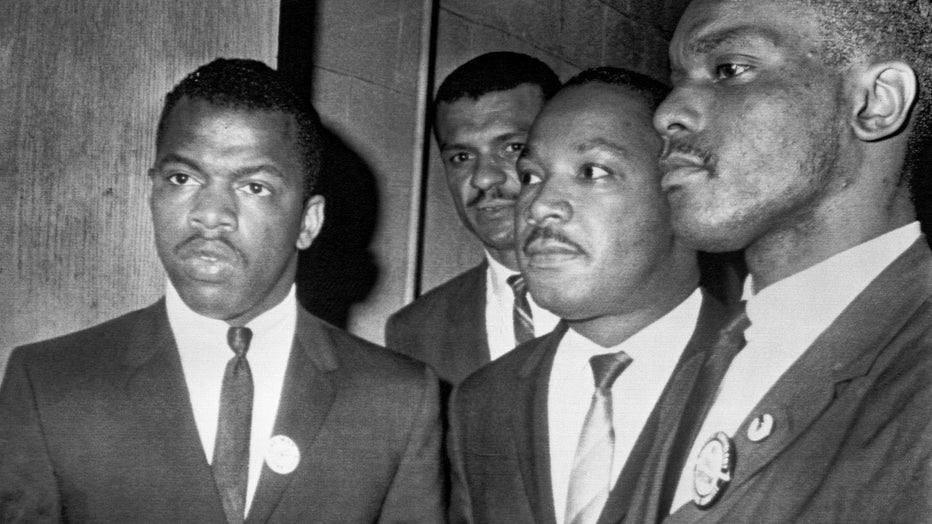

Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., (center) is escorted into a mass meeting at Fish University in Nashville. His colleagues are, left to right, John Lewis, national chairman of the Student Non-Violent Committee and Lester McKinnie, on of the leaders in

1964: Mississippi Freedom Summer

In June of 1964, John Lewis coordinated SNCC efforts to organize voter registration drives and community action programs during the Mississippi Freedom Summer, according to his biography.

When SNCC activist Robert Moses launched a voter registration drive in Mississippi in 1961, “he confronted a system that regularly used segregation laws and fear tactics to disenfranchise black citizens,” according to SNCC. It was during this time that Lewis helped create political momentum for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, according to his biography.

1965: March on Selma and Bloody Sunday

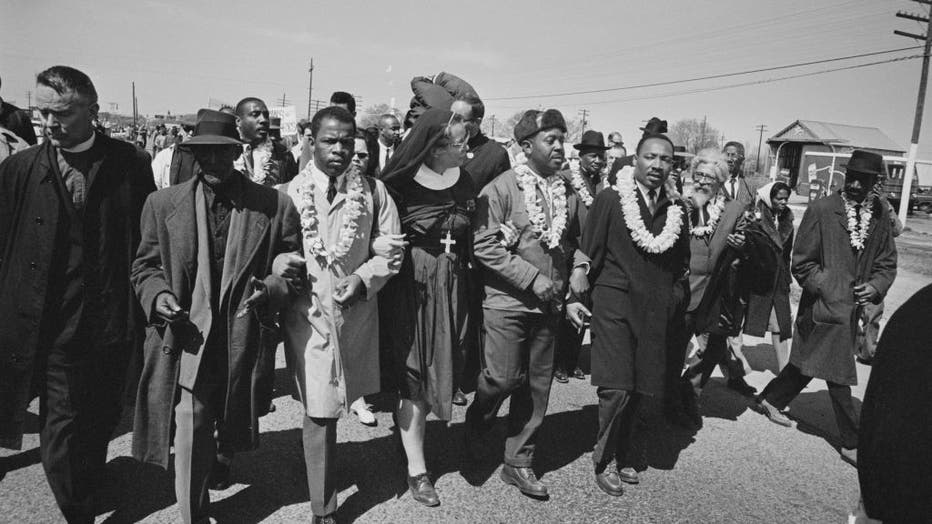

Lewis, as well as Hosea Williams, along with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., led over 600 peaceful protesters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama on March 7, 1965.

They intended to march from Selma to Montgomery to demonstrate the need for voting rights in the state, but marchers were attacked by Alabama state troopers in a violent confrontation that came to be known as "Bloody Sunday."

Dr Martin Luther King Jr., arm in arm with Reverend Ralph Abernathy, leads marchers as they begin the Selma to Montgomery civil rights march from Brown's Chapel Church in Selma, Alabama, on March 21, 1965; (L-R) an unidentified priest and man, John L ((Photo by William Lovelace/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images))

News coverage of “Bloody Sunday,” outraged the nation. Lewis, who was severely beaten on the head, said: “I don’t see how President Johnson can send troops to Vietnam—I don’t see how he can send troops to the Congo—I don’t see how he can send troops to Africa and can’t send troops to Selma,” according to The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

Despite more than “40 arrests, physical attacks and serious injuries, Lewis remained a devoted advocate of the philosophy of nonviolence,” his biography stated.

FILE - A sign marking the Selma to Montgomery voting rights march is seen on March 5, 2015 in Selma, Alabama. (BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

1966: John Lewis becomes director of the Voter Education Project

John Lewis left the SNCC in May of 1966 and continued his commitment to the civil rights movement as associate director of the Field Foundation, participating in the Southern Regional Council's voter registration programs, according to his biography.

He went on to become the director of the Voter Education Project (VEP) and was instrumental in adding nearly 4 million minorities to the voter rolls.

1977: John Lewis appointed to ACTION

John Lewis was the recipient of the Martin Luther King Jr. Nonviolent Peace Prize in 1975 and in 1977 and was appointed by President Jimmy Carter to direct more than 250,000 volunteers of ACTION, the umbrella federal volunteer agency that included the Peace Corps and Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), according to his biography.

“In 1971, the VISTA program was transferred from the Office of Economic Opportunity to the former Federal agency ACTION (the Federal Domestic Volunteer Agency). In 1973, Congress enacted the Domestic Volunteer Service Act of 1973 (DVSA), the VISTA program's enabling legislation,” according to the Federal Register.

The VISTA program continues to retain its purpose, as stated in the DVSA, “to strengthen and supplement efforts to eliminate and alleviate poverty and poverty-related problems in the United States by encouraging and enabling individuals from all walks of life, all geographical areas, and all age groups, including low-income individuals, elderly and retired Americans, to perform meaningful and constructive volunteer service in agencies, institutions, and situations where the application of human talent and dedication may assist in the solution of poverty and poverty-related problems and secure and exploit opportunities for self-advancement by individuals afflicted with such problems.”

1981: John Lewis elected to the Atlanta City Council

Lewis was elected to the Atlanta City Council in 1981 after leaving ACTION, and during his time serving on the council, he was an advocate for ethics in government and neighborhood preservation.

One notable action Lewis pursued during his first year on the council was to preserve the neighborhoods in Atlanta by opposing the Great Park plan

.Lewis was convinced that the road would negatively impact the neighborhoods through which it would pass, as well as the city as a whole, according to The Atlanta Weekly. He believed it would clog up downtown traffic and would further deprive the poor, black inner-city communities of opportunities. "I don't think the people in the mayor's office ever really thought about what this would do for Atlanta," he said. "To this day, I don't know anything that would justify building it."

"Almost from the first day of council I got in trouble, what I call good trouble," Lewis said in a 1982 interview with The Atlanta Weekly. "I think it was the first session of council, I introduced a resolution saying that 'Atlanta will go on record opposing a four-lane road through the Great Park.' It was passed unanimously by council, and the mayor signed it. Then one and a half, two months later, word came down that the mayor had a plan for a road. I was surprised, dismayed," Lewis told the newspaper. "I don't know, but my feeling is that even before the plan came into being, the mayor had made a commitment to President Carter and to [Department of Transportation Commissioner] Tom Moreland, that he was locked in and had to tell planners to include the road."

In the end, the Great Park plan, including the road, passed the City Council, with Lewis, Bill Campbell and Myrtle Davis, the three newly elected black council members, voting against it.

A smaller version of the road would eventually become Presidential Parkway, later renamed John Lewis Freedom Parkway in August of 2018.

1986: John Lewis is elected to Congress

Lewis was elected to Congress in November 1986, and had served as U.S. representative of Georgia's Fifth Congressional District since then.

Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., stands on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., in between television interviews on Feb. 14, 2015. Rep. Lewis was beaten by police on the bridge on "Bloody Sunday" on March 7, 1965, during a march for voting rights from Sel

He was the Senior Chief Deputy Whip for the Democratic Party and was also a member of the House Ways & Means Committee, a member of its Subcommittee on Income Security and Family Support, according to his biography.

He was also a key sponsor in many bills, including, but not limited to:

-Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Reauthorization Act of 2016 (H.R. 5067 114th)

-Medicare and Medicaid Extenders Act of 2010 (H.R. 4994 111th)

-National Museum of African American History and Culture Act (H.R. 3491 108th)

-Selma to Montgomery National Trail Study Act of 1989 (H.R. 3834 101st)

2001-2002: John Lewis awarded the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award and the NAACP Spingarn Award

In May of 2001, Lewis received the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award and in 2002, he was awarded the NAACP Spingarn Award, which is given “first to call the attention of the American people to the existence of distinguished merit and achievement among Americans of African descent, and secondly, to serve as a reward for such achievement, and as a stimulus to the ambition of colored youth,” according to the NAACP website.

2011: John Lewis awarded Presidential Medal of Freedom

On Feb. 15, 2011, President Barack Obama awarded Lewis the nation’s highest civilian honor, the 2010 Medal of Freedom.

"John Lewis is an American hero and a giant of the Civil Rights Movement," a statement issued by the White House read.

Obama echoed the sentiment. “There’s a quote inscribed over a doorway in Nashville, where students first refused to leave lunch counters 51 years ago this February,” Obama said during the medal presentation ceremony in 2011. “And the quote said, ‘If not us, then who? If not now, then when?’ It’s a question John Lewis has been asking his entire life.”

Rep. John Lewis is presented with the 2010 Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama during an East Room event at the White House February 15, 2011 in Washington, D.C.

“It’s what led him back to the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma after he had already been beaten within an inch of his life days before,” Obama continued. “It’s why, time and again, he faced down death so that all of us could share equally in the joys of life. It’s why all these years later, he is known as the Conscience of the United States Congress, still speaking his mind on issues of justice and equality. And generations from now, when parents teach their children what is meant by courage, the story of John Lewis will come to mind — an American who knew that change could not wait for some other person or some other time; whose life is a lesson in the fierce urgency of now.”

2019: John Lewis diagnosed with pancreatic cancer

It was announced in a statement on Dec. 29, 2019 that Lewis had been diagnosed with stage 4 pancreatic cancer.

“I have been in some kind of fight – for freedom, equality, basic human rights – for nearly my entire life. I have never faced a fight quite like the one I have now,” Lewis said in the statement. “This month in a routine medical visit, and subsequent tests, doctors discovered Stage IV pancreatic cancer. This diagnosis has been reconfirmed. While I am clear-eyed about the prognosis, doctors have told me that recent medical advances have made this type of cancer treatable in many cases, that treatment options are no longer as debilitating as they once were, and that I have a fighting chance. So I have decided to do what I know to do and do what I have always done: I am going to fight it and keep fighting for the Beloved Community. We still have many bridges to cross,” the statement continued.

“To my constituents: being your representative in Congress is the honor of a lifetime. I will return to Washington in coming days to continue our work and begin my treatment plan, which will occur over the next several weeks. I may miss a few votes during this period, but with God’s grace I will be back on the front lines soon. Please keep me in your prayers as I begin this journey,” Lewis said.

2020: John Lewis lends his voice to the calls for justice in the wake of George Floyd’s death

Lewis urged protesters seeking justice in George Floyd’s killing to embrace nonviolence and called on President Donald Trump not to crack down on “orderly, peaceful, nonviolent protests.”

“You cannot stop the call of history,” Lewis said.

Floyd, 46, died in Minneapolis police custody on Memorial Day. The moments leading to his death were captured on camera and spread across social media, igniting a chaotic, historic and emotional few weeks in the U.S.

The video showed Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin pinning Floyd to the ground and pressing his knee into his neck as Floyd repeated that he could not breathe. Floyd eventually became unresponsive and was pronounced dead at a local hospital.

Protests broke out across the nation and around the world, demanding justice and police reform in the wake of Floyd’s death.

What started off as peaceful demonstrations turned violent in many cities across the U.S., with one of the more notably violent riots breaking out in Lewis’ own city, Atlanta.

“Despite real progress, I can't help but think of young Emmett today as I watch video after video after video of unarmed Black Americans being killed, and falsely accused,” Lewis said in a statement on the protests. “My heart breaks for these men and women, their families, and the country that let them down — again. My fellow Americans, this is a special moment in our history. Just as people of all faiths and no faiths, and all backgrounds, creeds, and colors banded together decades ago to fight for equality and justice in a peaceful, orderly, non-violent fashion, we must do so again.”

“To the rioters here in Atlanta and across the country: I see you, and I hear you,” the statement continued. “I know your pain, your rage, your sense of despair and hopelessness. Justice has, indeed, been denied for far too long. Rioting, looting, and burning is not the way. Organize. Demonstrate. Sit-in. Stand-up. Vote. Be constructive, not destructive. History has proven time and again that non-violent, peaceful protest is the way to achieve the justice and equality that we all deserve.”

In an interview with local media, Lewis quoted Martin Luther King Jr.: “Hate is too heavy a burden to bear. The way of love is a much better way.”

“During the ’60s, the great majority of us accepted the way of peace, the way of love, philosophy and discipline of nonviolence as a way of life, as a way of living,” he continued. “There’s something cleansing, something wholesome, about being peaceful and orderly.”

RELATED: 'It's very moving,' civil rights icon John Lewis visits Black Lives Matter Plaza

“We’re one people, we’re one family,” he said in the interview. “We all live in the same house, not just the American house but the world house.”

Lewis also expressed support for H.R. 7120, the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, that passed the U.S. House of Representatives by a vote of 236 to 181 on June 25, according to a news release from his office.

“Many may seek to mischaracterize this legislation. Some will ignore the opportunities that this bill presents to improve our communities,” Lewis said in a statement. “For example, I greatly appreciate that the authors included my proposal, the Law Enforcement Inclusion Act, which permits Federal grant funds to be used to recruit and train officers from the neighborhoods they are charged to protect and serve. H.R. 7121 also provides law enforcement with the help and training they need to address mental health, drug use, and other complex societal issues. These proposals are partial solutions to the historic disconnect and distrust between communities of color and law enforcement.”

“Others may argue that the bill does not go far enough,” Lewis continued. “This legislation addresses one Federal part of a complicated puzzle of entrenched, systematic bias and inequality, and we cannot let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Going forward, we must demilitarize law enforcement and establish empathy in our justice system. Make no mistake – much more is needed from cities, counties, State, and Federal authorities in every corner of our country. Our work is cut out for us, and our mandate, from those whom we were elected to represent and serve, is clear.”

The Associated Press and FOX 5 Atlanta contributed to this report.