Minnesota Untold: I-35W freeway uprooted and divided African American business district

The construction of Interstate 35W ripped up Black communities in Minneapolis.

MINNEAPOLIS (FOX 9) - Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg announced plans to address racial inequities in the U.S. highway system. His agency will use nearly $1 billion to redesign highways that decades ago, devastated communities of color.

The original Rondo neighborhood in St. Paul was destroyed when I-94 was constructed through the area starting in 1956. The lesser told story is what 35W did to the African American Business district in south Minneapolis.

Minnesota Untold: I-35W freeway uproots and divides African American business district

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg announced plans to address racial inequities in the U.S. highway system. His agency will use nearly $1 billion to redesign highways that decades ago, devastated communities of color.

At the corner of 38th Street and 4th Avenue in the Central neighborhood, the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder newspaper remains one of the last remnants of a once-thriving business district.

"This was a big, huge Black community at that time," said Tracey Williams-Dillard, Publisher and CEO of the Spokesman.

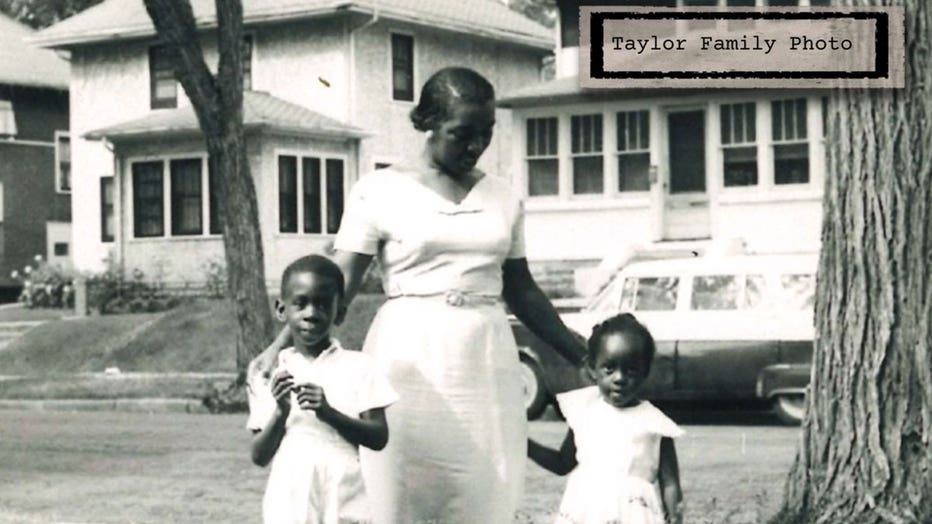

Williams-Dillard's grandfather founded the newspaper in 1934, she recalled growing up there as a child.

"This whole corner was all Black-owned and a lot of the businesses up and down the street, they were Black-owned businesses," she reminisced.

A record store, a bank, barbershops, salons and grocery stores were some of the businesses that occupied the 38th Street landscape in the 1950s. But the community would undergo a seismic shift, that some didn’t see coming.

The passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act in 1956 allowed for the building of a 41,000-mile interstate highway system throughout the country.

The federal government provided 90 percent of the funding in the Twin Cities to build I-94 and 35W.

During a time of economic growth and growing mobility in the country, the freeway system would revolutionize transportation, but it came at a cost.

African American community unaware of freeway plans

Dr. Ernest Lee Lloyd holds a doctorate degree in Public Administration and wrote his dissertation examining 35W and the disruption it caused middle-class working African Americans.

"One of the elders. Elder Harry Davis said to me, Ernest it’s like he used the French word ‘l'acte est fait,’ which means that the deed is done. It was already done before we knew about it. It was done years before that," Lloyd said.

Many of the residents owned homes in the south Minneapolis neighborhood.

"The African American, the elders, and they were prominent African Americans living at that time in Minneapolis. They said they had no idea what was going on until a bulldozer came in tearing down trees and moving dirt," he recalled from his research.

Running between 2nd Avenue and Stevens Avenue, today, 35W links downtown Minneapolis to Highway 62.

Thousands of homes and businesses in the interstate’s path were destroyed or removed.

"Every pocket of African American neighborhood, urban area, in the United States, you will find a highway border them, splitting them up or dismantled the entire community altogether," Lloyd told FOX 9. "Why would transportation policy, which is racist in itself, would disrupt and destroy a neighborhood like this?"

When asked if it was intentional, he replied, "To say that, was it intentional? It hurts me to say yes, it hurts me to say yes."

It's estimated that nearly 30,000 people throughout the Twin Cities lost their homes to freeway construction.

Other locations considered for 35W

"You know, this is a pattern that is taking place," said Associate Professor Greg Donofrio, who is the Director of the University of Minnesota’s Heritage Studies and Public History program.

He was led to Lloyd's research while conducting his own comprehensive study of 35W.

"The racial disparities that we have here in the Twin Cities, in Minneapolis, and in Minnesota, they didn't just happen. They're not natural. These conditions were created," he said.

According to Donofrio, other locations in south Minneapolis were considered for 35W including Cedar and Lyndale Avenues, streets that he said were in wealthier, white communities at the time but they were ruled out early in the planning process.

One photo, dated March 12th, 1957 in Minneapolis, documents the only known public hearing on the interstate project.

Photo showing construction for the highway.

"So, you know, this isn't to say that only people of color were affected by the freeway and its construction, but people of color, Black people were disproportionately affected, and they had a terribly difficult time finding housing," Donofrio said.

It's estimated that nearly 30,000 people throughout the Twin Cities lost their homes to freeway construction. Over the course of the 10-year project, through eminent domain, the state government forced some people out of their homes, others were paid to leave. Already burdened by discriminatory housing practices such as racial covenants and redlining, people of color were hit especially hard.

"You know, when we started this project, we were looking for smoking guns. We're looking for one document that says we place the freeway here because it's going to displace Black people. You're not going to find that. We concluded two years later and you're not going to find that because this is a manifestation of systemic racism," Donofrio said.

An eight-millimeter digitized home movie, taken by the Scott Johnson family, in front of a house on 43rd and 2nd in the 1960s captures the 42nd Street Bridge and the pedestrian bridge at 40th Street East.

With no 35W entrance ramp, the freeway cut off direct access to 38th Street which many believe devastated the once vibrant African American business district just three blocks away.

George Floyd Square at 38th and Chicago on the morning of April 20, 2021. (FOX 9)

Focus now on 38th and Chicago

Minneapolis City Council Vice President, Andrea Jenkins is behind a plan to revitalize the area with a focus on the intersection of 38th and Chicago, the site where George Floyd was killed.

"Right now, MnDOT is doing a study to determine whether or not those families even got the fair market value for their homes as they were being displaced, because there is a pretty significant theory that they did not," the Council Member said. "I mean, I think the state has to play a role in righting those wrongs and as does the city. And I think the first step in that is to acknowledge the harms."

Greg McMoore is a long-time resident and neighborhood advocate.

"I think there's a chance, you know, I think there's a chance for 38th Street and 4th Avenue to come back. And many believe that opportunity may start just a few blocks away at George Floyd Square. If we approach it correctly, there's an opportunity," he told Fox 9. "You can't live in the past, but you can learn from it."

The research that Professor Donofrio led is on display in an exhibit at the Hennepin History Museum.

It's called, "Human Toll, a public history of 35W."

It runs until October 2022.