Black History Month: Black Rosie the Riveters at Minnesota WWII Plant

The Black 'Rosie the Riveters': The women of color who broke barriers during WWII

Historians are uncovering the role women of color played in the effort on the homefront during World War II.

EDEN PRAIRIE, Minn. (FOX 9) - The lessons of World War II are stored in volumes of books and newsreels. But one of this country’s rich stories during the war effort was the often overlooked contribution of Black men and women in the factories and offices of production plants across the country, especially in Minnesota.

One of those vital workers was the daughter of an escaped slave, Hazel Curry.

"Hazel was, they say, the first Black female graduate of Davenport, Iowa," recalls her grandson James Curry.

Like many Black families during the great migration after the U.S. Civil War, Curry’s family initially settled in Iowa. As a pioneering high school graduate, Hazel became an equally pioneering college student graduating summa cum laude from Wilberforce College in Ohio. Wilberforce is considered the nation’s first Historically Black College or University.

"Yeah, a good catch," said James of his grandmother. "Smart, and independent, and active in the community and civics."

She was also fluent in French and dreamed of traveling to France. The closest she got was through a U.S. Army soldier who fought in France in World War I who she happened to notice one day.

There’s a story that she said in French, ‘Boy, I’d love to give that guy a kiss.’ And since he had served in France, he knew French, so he swept her off her feet and gave her a kiss," recalled James. They married. The Curry’s had eight children and settled in the Twin Cities.

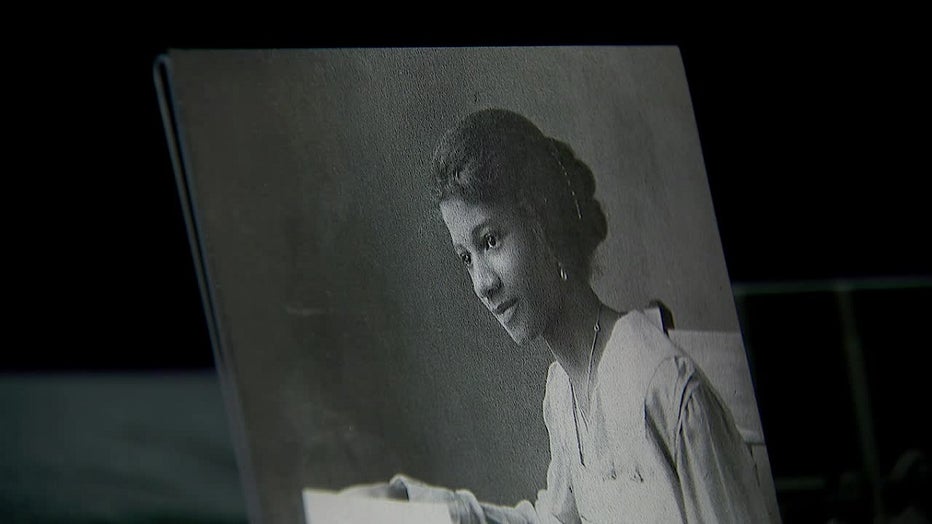

Pictured is Hazel Curry. (Credit grandson James Curry) (Supplied)

When war broke out again in 1942, the nation quickly turned factories into war production plants. And here again, Hazel broke more barriers by becoming among the first Black women to join the production lines.

"You know, this story is under told," said Jeremiah Ellis, a historian and Arthur S. McWatt Fellow with the Ramsey County Historical Society. "They were part of a huge effort of making the United States able to win the war."

Hazel Curry was part of the efforts to integrate war production at the Twin Cities Ordinance Plant in Arden Hills. The War Department contracted with the Federal Cartridge Corporation to manage the plant and produce 30 and 50 caliber ammunition for U.S. soldiers to use in battle.

"There was a public push on this ordinance plant as well as other plants to integrate," said Ellis.

The pressure came from leaders in the Black community, and in the Twin Cities, one of the biggest voices also spoke with barrels of ink. Cecil Newman was the owner and publisher of the Minneapolis Spokesman and St. Paul Recorder, two of the Twin Cities’ leading Black newspapers.

Newman was also deeply involved with the Urban League. Newman found a receptive ear in the president of Federal Cartridge, Charles Horn. Not only did Horn subscribe to Newman’s papers, but he also put Newman in charge of what was called the office of Negro personnel at the ordinance plant. Newman hired Ethel Maxwell Williams as his assistant.

"Her role, her position was to ensure the success of African-American employees in being in an integrated workforce," said Ellis.

In a 1944 article Newman wrote for the national Urban League magazine Opportunity, he reported the number of Black employees, "grew rapidly to about 1,000 at peak of employment." He also proudly reported he had, "Negro men and women working in 11 different departments in 32 different job classifications."

"We think of Rosie the Riveter, and we think of that white face with the red bandana female face, but it was a multicultural thing," said Hazel Curry’s grandson.

The stories of Black Rosie the Riveter is now getting new exposure from a documentary called "Invisible Warriors: African American Women in WWII." The film will premiere at the Minnesota History Center on Saturday, Feb.11 during a program that starts at 1 p.m.

"One of the things I’ve deliberately done is to expand the understanding of who Rosie’s were," said filmmaker Gregory Cooke. "There were 600,000 African-American Rosie the Riveters. And they did basically whatever men were doing prior to the war."

"WWII, in my opinion, was the most significant time period and the most significant event in the 20th Century for African-Americans," explained Cooke. He reasons that war production work meant opportunity. Many of the Rosie’s were making $40-50 a week. For Black women that meant considerable economic power.

"They brought millions of dollars into the Black community. They went on to spearhead the civil rights movement. And they were a major foundational block to helping establish and reinforce the Black middle class after WWII," said Cooke.

At factories like the Twin Cities Ordinance Plant, integration not only worked, it became a model for the rest of the nation. The Pittsburgh Courier, a prominent Black newspaper with nation-wide distribution via the railroads, reported on the hiring taking place at an ammunition plant in Twin Cities. To Ellis, the articles carried a clear message. "That there might be opportunity, there might be a better life for me in Minnesota," he said.

More than 70 years later the story still resonates, especially with Hazel Curry’s grandson.

"It’s a story to be celebrated. It speaks to the multi-threaded quilt that is America," said James Curry.